The Year We Lost Touch

It has been QUITE a year. This month we look back at all we lost with comedian Laurie Kilmartin, 'Booksmart' screenwriter Emily Halpern, and even...you. Yes, you.

I get chills when mid-August hits despite the oppressive late summer temperatures. My body knows to brace itself for what I call anniversary season. The last time I hugged my mom. The last blissfully ignorant laugh we’d share. The day she died, September 4, that cleaved my life into The Before and The After. You know what I’m talking about.

Right now, we are all in the COVID-19 anniversary season. Our bodies and minds have been bracing themselves for a while now, and with good reason: Because it’s something that deserves to be honored and examined and lamented. Even if we aren’t grieving the death of someone over the last year, we’re all grieving something that we desperately wish we could have back. The loss of freedom, of perceived control, of identity and education and childcare and health and sleep and jobs and security and community. And, of course, the loss of comfortable, easy touch. That beautiful thing with the magical power to make us feel better. We’ve lost it for now, and it’s my greatest hope that we will get it back soon.

This newsletter issue is – as my 7-year-old would say - a bit of a “longy.” But that’s because it’s an important one meant to throw into relief the human toll of this global pandemic that has killed 2.6 million people worldwide and, if you go by the bereavement multiplier, launched a grief pandemic currently suffered by 23 million from COVID-19 deaths alone.

So please take your time reading, because there’s an enormous amount of beauty below. We start off with a let-it-all-hang-out interview with CONAN writer and co-host of The Jackie and Laurie Show podcast Laurie Kilmartin. Her mother died alone in a hospital last June after contracting COVID-19 in a nursing home, and Laurie took to Twitter to document an unfiltered end-of-life and grieving process.

Next, a photo essay by four people whose loved ones died in relative isolation from this new virus. Their poignant narratives encompass distanced goodbyes, what could have beens, and even the January 6 attack on the United States Capitol.

And finally, a deeply personal essay by Booksmart screenwriter Emily Halpern (if you need some poignant comic relief after this week, may I recommend this masterpiece? It’s basically perfect, just sayin’…) as she connects the feeling of abandonment after her father’s accidental death with a similar one that’s arisen during the pandemic.

I’ll leave you with my deep gratitude for being part of and supporting this Modern Loss community. It hasn’t been an easy year for anyone, including over here. When the pandemic slammed into our lives last March, we halted all plans for in-person events and immediately started offering virtual support sessions ranging from a therapist- and expert-led (incidentally, a good time to recognize all of the incredible mental health workers who have shouldered our individual and collective grief this year) to creative author talks to wellness events to keep you sane during this weird isolation. We flew by the seat of our stretchy at-home pants in order to provide ongoing connection points. A year later, we’ve offered more than 35 of them, with many more to come.

If you believe in our mission and how much work goes into it, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. You’ll receive numerous benefits and get 20% off annual memberships all month in honor of this sensitive time. Your support enables us to continue to generate high-quality content that pulls us all in.

– Rebecca Soffer

“Wear A Fucking Mask”: Comedian Laurie Kilmartin on Grief, Humor, and Loving Your Trump-Supporting Mom

Rebecca Soffer: Your mom, Joanne, became ill with COVID after she was transferred to a nursing home. Was there any difference in the experience of grieving your dad’s death and that of your mom’s?

Laurie Kilmartin: Their deaths were so different. My dad had home hospice, everyone that ever met him came to visit. They all told stories. He heard everything and he was conscious till maybe four hours before he died. He was surrounded by love. And we converted the whole living room into a place where he could just look at pictures and it would be the death that I would want.

RS: Like what they call a good death, right?

LK: Exactly. And then my mom, alone, unconscious for a couple of days. My sister and I have no idea if she heard a word we said to her, despite the fact that we talked to her constantly over FaceTime. And the hour and a half we were allowed to visit her in person we don't know if she heard us. When we were in her hospital room she did sit up and kind of roll her eyes up. She was trying something. And I've always been trying to figure out what she was trying to say...but I'll never know.. She didn't get to have last words. She didn't get anything my dad had. And she got screwed over big time with the way that COVID takes you.

RS: When you think about the worst part of her end-of-life experience, what comes to mind?

LK: That she was alone in a hospital...a place she'd never been before. And the place before that was a piece of shit nursing facility where she got COVID. The last two places that she got to be alive are pretty bad.

RS: You’ve said your relationship with your mom was complicated. She was a Trump supporter. You’re not. A lot of us can relate to grieving someone with whom not all the things were said, not all the amends were made. Ends were left untied.

LK: We went to therapy before she got COVID...and I just realized it's never going to get better. This is her. And if anything, she's getting a little more closed and not open, and that's that. And I'm never going to get that feeling of being seen from her like you need from a mother. I'm getting as much as she's able to give. And like you said, not all loose ends will be tied. Many of them will be permanently loose.

RS: Do you turn any of that over in your head now?

LK: This is what I do a lot [SIGHS LOUDLY]. I talk to her best friend a lot. She’s 85 and still with it and a Democrat. I try to get some perspective on her via that. And I do feel regret. I wish I hadn't got into the last three political fights, but I don't know how that would've happened.

RS: Ah, politics. At Modern Loss, over the last year, we’ve occasionally heard “I come here for grief. Stay in your lane. Don't get political." And that’s about our comments on, say, believing in masks or wanting empathy in the White House during a pandemic killing hundreds of thousands. In my opinion, the personal is so political these days. What do you say to anyone who says you're politicizing grief?

LK: I’d say your politics caused my grief. I’d say your politics took a couple of years of grandmothering away from my son. She would’ve been able to see her grandson get his braces off, which is all she wanted. You defend your politics to my grief, how about that?

RS: You're a comedy writer. What does humor do for you?

LK: When you're writing a joke you're just trying to manage an emotion or a situation and make it have the outcome of a laugh, as opposed to the outcome of dread. For me, it was helpful to have these little things bubble up during my mom's situation. And then wrap it up in a little comedy bow and put it out there and move on. Because feelings and things I would notice would come and go so quickly that it just helped me to save them and then go to the next one.

RS: You're live-tweeting about your mom's end of life and death. People are moved and engaged and respond. What does it do to have witnesses to your experience?

LK: It's weird. I’d tweet jokes about the act of watching someone die remotely. And people would respond with heart emojis or hugs. And I'm like, I'd rather just not hear anything. I get that you can't write lol or haha, your Mom's dying. You could just like it. I think people don't know what to say when you're joking about something in that situation. But you don't have to say anything.

RS: What kind of effect do you hope you’ll have on the public discourse on grief and how we can support each other in general during this time?

LK: At the time [COVID] was pretty new so I hoped people reading would go, oh, this is bad. Okay, I'll wear a mask, I'll call my mom and make sure she wears a mask. Also, a lot of people my age had older parents that were like, nah. I hope some of them started getting more serious after they followed me through my mom's getting it and dying from it.

RS: You had a Zoom funeral for your mom. How was that?

LK: My mom was from Chicago and had some friends from high school that were still alive and their children helped them log on. We did have a lot of people tuning in that would not have been able to travel, even if there were no COVID restrictions. And that was nice. We were able to record it. I haven't watched it since, but I'm sure I will again one day. I liked that part of it.

Of course, there were some people that didn't log in. But I'm like, you had no excuse and I'll remember this when we see each other in person again.

RS: Right. You always remember who didn't come to the funeral. But if you didn't log into the Zoom, I mean, are we in agreement that that's literally the lowest baseline for showing up?

LK: Yeah. Put the picture up and go on mute, just be there. I won't know if you're listening or not! I mean, yeah, there's a couple of cousins I will give the stink eye to at Thanksgiving.

RS: What's your reaction that some states and cities are now fully open for business?

LK: I want to bomb that city or state, knowing full well there's plenty of people who don't want that, either. There are so many comedians that turned out to be anti-maskers. I'm like, how will I handle seeing these guys back in comedy clubs? Am I just going to be cool or is there going to be some rage that pops up and all of a sudden I go off. I don't know, it's kind of exciting, we'll see. There might be some video of me just screaming at somebody.

RS: After your mom died, what's the best thing that somebody you know said or did for you?

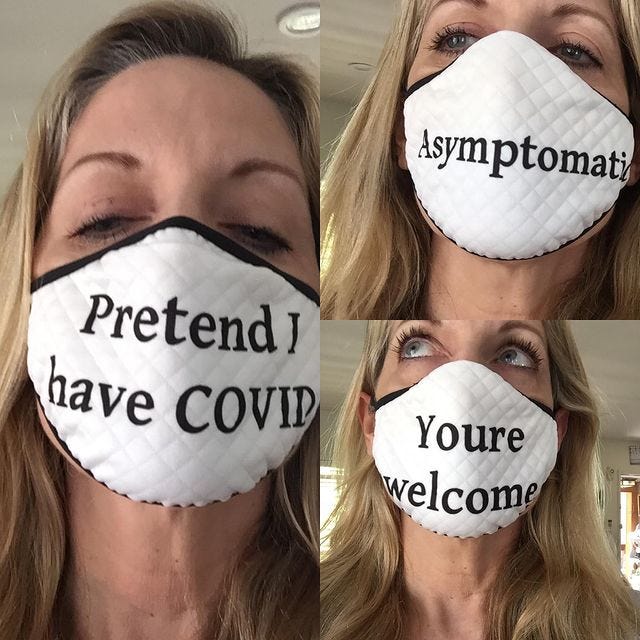

LK: The best thing? My best friend Cheryl sent me 16 masks that say “My mom died of COVID four fucking days ago, wear a fucking mask.” I mean, it was in really tiny font because she had to put it all on there, but I loved it.

The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

It’s Personal: Portraits of COVID Grief

The story of my mom’s 40 days in the hospital is one of distance. She lived her life willing to travel anywhere for family and friends. But in the end, we couldn’t even hold her hands.

My mom died from COVID-19 on January 6, 2021—in the very moments that our Capital was under siege, 200 miles away. The story of her death is entangled in a larger, murkier story, with millions of others and their families; casualties of war and heartbroken survivors; betrayal, neglect, ignorance. God willing it’s a story of resilience and healing, but not yet—not even close.

The last phrase she ever said was “group hug.” The last lone word she said was, “love.”

The day after she died, I picked up her things at the hospital and found a tiny purse, inside of which were four rose quartz hearts. Now they belong to her grandchildren, Caleb and Carmel.

– Matthew Soffer, Durham, North Carolina

For the last 30 years, our lives had drifted apart, but we were finally building something. Alzheimer’s had deteriorated my mom's mind, yet, incredibly enough thanks to that, we were having a relationship at last. No more arguing, rebukes, blame.

Enjoying the small things of life was becoming possible. All of that was literally destroyed overnight: Sunday evening everything was ok. Monday morning she was so unwell that I had taken her to the hospital. I didn't even say goodbye. By the time I signed the administrative papers, she had been taken to the COVID-19 wing.

For a while, I left her bedroom exactly as she left it. I truly believed she would survive; she was so strong. Everything went so fast and so slow at the same time. I feel I've been robbed. A part of my identity is lost forever.

A chapter in my book will remain incomplete.

– Carolina Díaz Marquet, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

What is the strangest thing you could ask for when your mom is dying? I couldn’t be there. I still feel the deep pain of that. I could FaceTime, though. (How strange is that statement?) But I didn’t want to see her face riddled with sick, intubated, covered in wires and gray with less and less breath. That wasn’t my mommy. I didn’t want that to be the last indelible image in my mind. I wanted to look at what I knew from my very first moments of life. What comforted me when I was sad, disappointed or frustrated. Cheered for me for my biggest achievements and even the simplest ones. What protected me from danger even just crossing the street. What I can still feel even to this day in their absence. Her hands. Her soft, loving, with painted nails, wonderful hands. So that’s where the camera went. And there she was. They didn’t look sick or captured by this horrible disease. They looked just as soft and beautiful and for one last time, with her last breath, she comforted me. – Taifa Harris, New York City

My brother, Luis, died alone from COVID-19 on March 31, 2020. We didn’t get to say goodbye. We didn’t get to tell him how much he meant to us and how much he was loved. I had to be the one to tell my family he died. I can still hear my dad’s wailing in my head and the destroyed look on my sister’s face. I had to pick an urn online and have my husband then drive it from Long Island to Staten Island to the funeral home. There was a two-week wait for cremation because the morgues were that full. We haven’t been able to have a memorial or anything. I am so incredibly angry. I am angry at the mismanagement by the former administration. I am mad at those who think this is a joke and their rights are being infringed upon by wearing a mask. I am angry my children won’t grow up without their uncle who loved them so much. Luis is more than just a number. He was a son, a brother, an uncle, a friend, a godfather. He was incredibly kind and intelligent. He almost died as a baby due to a surgical mistake – he got held up at gunpoint as a young adult – and what did him in, was this. The cards were always stacked against him. – Kasandra Raux, West Babylon, New York

Join Us 3/16 for a Therapist-led COVID session

Join two friends as they discuss similar paths taken from different points of view, helping clients walk the unique journey of loss. As the pandemic has awoken grief in so many corners of our lives, they will share our stories and invite you to bring yours.

Led by Millet Israeli, LMSW, a psychotherapist who works primarily with individuals and families struggling with grief, illness, end of life issues, anticipatory loss, and ambiguous loss; and Cressey Belden, a spiritual advisor who covers the gambit of the human experience with a special focus on grief and loss.

This event and all our virtual sessions are open to paid subscribers, who can register for our March sessions here. Through March, we’re offering 20% off annual subscriptions.

My Father, the Pandemic, and Thoughts on Abandonment

by Emily Halpern

When I was fifteen years old, my father died suddenly in a hiking accident. He left one winter morning for a day hike on Mt. Eisenhower, one of the many peaks comprising the White Mountains in New Hampshire. While on the mountain, he became trapped in a sudden blizzard, grew lost and disoriented, and eventually succumbed to hypothermia. His body was discovered three days later, perched on a rock; his feet were dangling in the stream he’d been following, trying to get home.

It’s common for a present trauma to trigger past trauma. And I’ve found myself thinking a lot about my father since the pandemic began. Over these last several months, memories and thoughts of his death have visited me more frequently than in recent years.

This year in quarantine has summoned many of the same emotions I’d felt back then: fear, anxiety, paralysis, vulnerability. My father’s death abruptly exploded the notion that I or anyone I loved was immune from arbitrary dangers. The pandemic has done this on a global scale.

My father’s death abruptly exploded the notion that I or anyone I loved was immune from arbitrary dangers. The pandemic has done this on a global scale.

But I think there’s more to it than that. My past has reasserted itself with a familiar, specific, and undeniable feeling. It’s one I recognize because I know it intimately: the feeling of having been abandoned.

My father was a gentle, comforting and giving person. He was also my idol, my companion, and my frequent hiking partner. We spent many mornings hiking trails in and around Lincoln, Massachusetts, my picturesque New England hometown. I adored him.

He had intended to come home that night. He was an avid hiker with experience hiking in all conditions. He loved me, my brother, and my mother, and would never have consciously put his life at risk. I believe that now, and I believed it back then. But all the believing in the world didn’t change the way I felt. My understanding of his intentions, unfortunately, was irrelevant, because logic occupies no space in grief. I had been wounded on a biological level. My father, the person entrusted with my safety and protection, left the house one morning and never came back. The message I received is that I wasn’t worth sticking around for. And the psychological toll this took was significant.

Read the full piece on our website.

Modern Loss’ newsletter is brought to you this month by the new film SOPHIE JONES, a new sensitive and utterly relatable coming-of-age story set apart from others by its true experiences of grief, girlhood, and growing up. Jessie Barr's quietly brilliant debut feature is available on VOD platforms like AppleTV, and in Virtual Cinemas to support independent theaters nationwide. Learn more here.

Thank you to our Founding Members

Uplift Center for Grieving Children

Pria Alpern, PhD

Ruth Ann Harnisch

Tim Federle

Amanda Johns Perez

Audrey Beerman

Betsy Hook