The Bonds That Hold Us

Siblings Day is here. "Go the F*ck to Sleep" author Adam Mansbach talks about brotherly ties, mental health stigma, and how A Tribe Called Quest partly inspired his new book.

In this Issue:

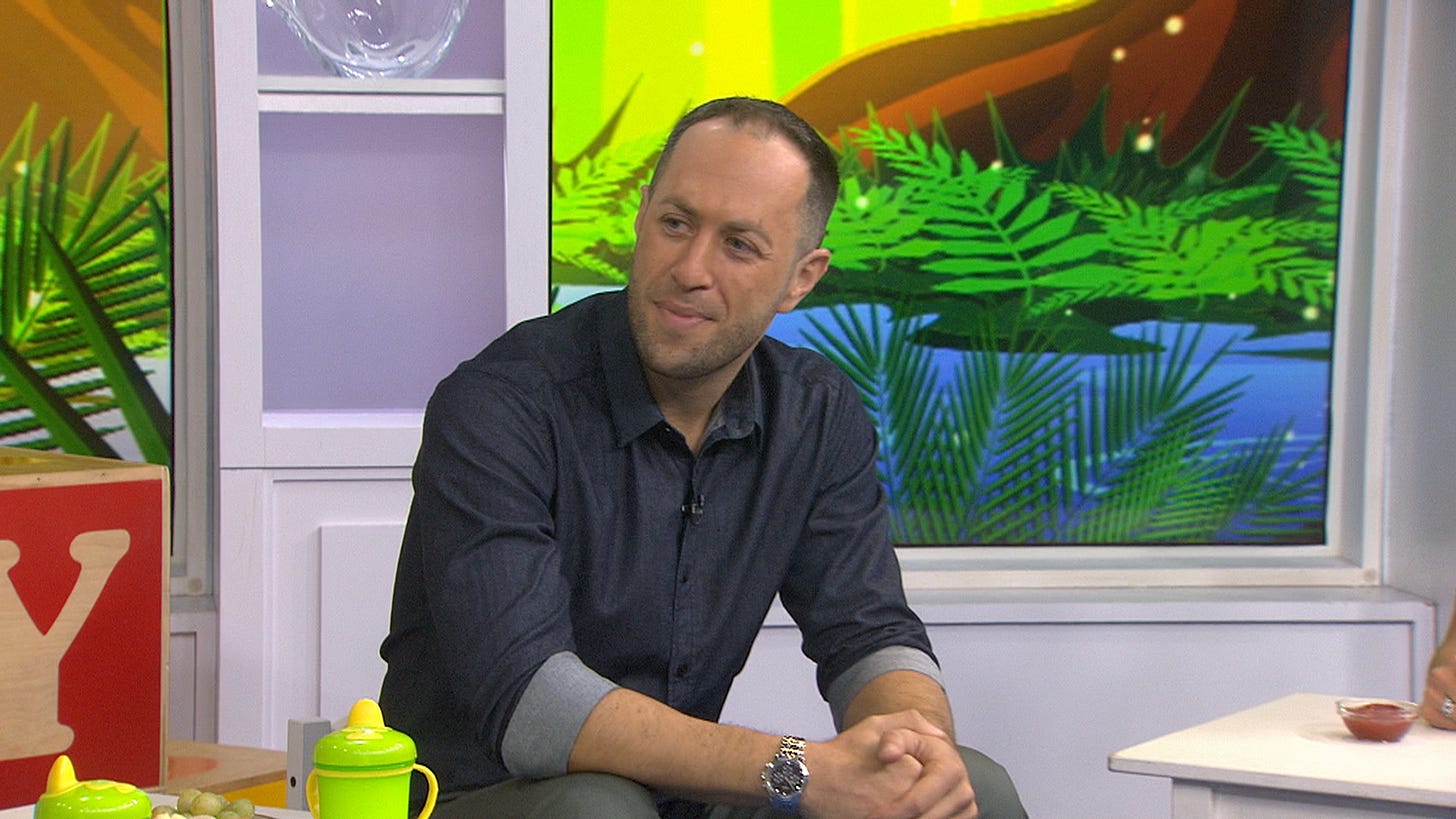

📖 An interview with I Had a Brother Once author Adam Mansbach

👧👧 What Siblings Day Means to Someone With a Dead Sister

📆 Register for our 4/14 mindfulness session & 4/29 communal baking

Today is Siblings Day. And probably like you, I had no idea it existed, either, until a couple years ago, when I saw it plastered all over Instagram.

What was interesting for me to learn – and what I assume most people don’t know – is that this particular day stemmed from one woman’s experience with profound loss (more about that below).

So during a day when your social media will be bursting with photos of happy, mostly alive siblings, we want to make sure that those with dead ones feel seen. Since launching Modern Loss in 2013 we have heard from thousands of people who say that they feel marginalized; as though sibling loss weren't as important or talked about or respected as other types of relationships. They feel alone in their grief frequently and like it's hard to connect with other people moving through a similar loss.

Well not here.

Below, we speak with New York Times bestselling author (remember the brilliant Go the F*ck to Sleep?) Adam Mansbach about his beautiful new book, I Had a Brother Once: A Poem, A Memoir, inspired by his brother David’s death ten years ago. And Kellyn Shoecraft beautifully illustrates in both words and cartoons an ode to those who find themselves moving through life with a piece of themselves forever missing.

And as always, we go even deeper on our website. Just handful of our sibling-related pieces include a woman who created an IG account as an outlet where she could post the dumb, hilarious minutiae she’d normally share with her brother, the complicated feelings of being grateful your dead asthmatic brother didn’t have to endure the pandemic but absolutely not grateful that he’s dead, the start of a global cookie-baking social media memorial holiday in the wake of a young sister’s car accident, and how having a dead sibling is full of contradictions.

If you’re participating in our Siblings Day gift swap – so many of you are! – remember to post your experience to Instagram and tag @modernloss so that we can share with the rest of the community.

And finally, check out upcoming April events, unlimited to our paid subscribers.

All my best for a safe and sane weekend.

- Rebecca Soffer

Adam Mansbach on Mourning a Life Witness, Toggling Between Extremes, and (Finally) Creating a Meaningful Ritual

Rebecca Soffer: You have a brother, his name is David. Tell me what happened.

Adam Mansbach: My brother died almost ten years ago and took his own life. He died at exactly the moment when [Go the F*ck to Sleep] was coming out. So I was balancing this private kind of bottomless grief and shock with this moment of public performance of joy.

I was doing TV and interviews on a daily basis for the next year. And toggling between these two extremes, there were a lot of ways in which suicide puts you in a place where your grief is outside of the mainstream of grief. A lot of the rituals around mourning and grieving and suffering are not really applicable to suicide, or at least they're much more complicated. Like, how do you mourn the loss of someone who chose to leave? How do you celebrate the life of someone who didn't think their own life was worth celebrating or continuing to live? So, grappling with David's suicide was tricky for all of those reasons and also complicated by the fact that I was privately dealing with all of that while very publicly doing this whole other thing.

RS: Which is so full of joy and humor. The dichotomy is insane.

AM: The dichotomy was insane. And there were times when it felt dishonest, like by omission I was lying. And every time I did an interview, particularly on camera, the thought would flash through my mind like, "What if this person asks me about my brother? What if the Today Show blindsides me with the question?" Which doesn't make any sense. That's not good television. Nobody benefits from blindsiding the luckiest asshole in the world with a question about his brother's suicide. But it still kept popping into my mind that this would happen.

RS: The way in which David died has been something that you’ve had to fold into your daily life and come to whatever sort of peace you can find.

AM: Yeah. The fact that he killed himself is absolutely inextricable from my understanding of his entire life. One of the really difficult things to deal with is that my brother was not forthcoming at all about being depressed. It was something he was ashamed of and kept hidden. There's a way in which it forces me to kind of look back on every interaction with him and every assumption, everything I thought I knew about him, and question it and see it in a new light and wonder whether he was the guy that I thought he was.

For me, the struggle is attempting on some level to understand what happened and why my brother did what he did and was who he was without entirely investing in that narrative, and without acting like it is something that I can or will understand.

RS: Did you always plan on writing about this experience?

AM: I always knew I would write about him. And yet, for eight years, I wrote everything else and was very prolific in that time. It felt like everything else I was doing – a screenplay, a humor book, a novel – was in avoidance of writing this piece. I don't think I was emotionally ready. And I also couldn't figure out the form.

RS: So what was the catalyst, eight years later, when you were like, "Oh, this is the time, and poetry is the genre”?

AM: First, I was commissioned to write a poem for the San Francisco Jazz Festival where a number of writers were performing with a live band. And then, Phife from A Tribe called Quest had recently died. So I wrote an elegy to Phife, because that was a death that hit me. And it kind of got me back in touch with the power of poetry at its best. My brother would have turned 40 that week, on April 18.

So I sat down and I started writing this book and dispensed with all the concerns about structure and scaffolding that had stopped me before. And I suppose I was emotionally ready to at least begin. The form was very liberating. It really did let me move freely and write only what I needed to without worrying about how one idea might connect to another.

My brother's birthday is always a hard day, as is the day that he died, which is May 28. By May 28 in 2019, I had this book and that day felt very different for me.

RS: How so?

AM: I felt not unburdened, but able to look it in the eye in a different kind of way. Usually, I can feel May 28 coming in the tilt of the planet and the way that the air smells. And there's this sense of dread of like, "This day is coming and I'm not equipped for it because I'm never equipped for it. I just have to get through it." And I didn't feel quite the same. It's like I have this thing, this testament. I enacted the first ritual that I've succeeded in making meaning from in the aftermath where there's death.

RS: Yeah. I call it anniversary season. Your body knows even before your mind knows when it's looming. How has your nuclear family dealt with grieving the same person differently?

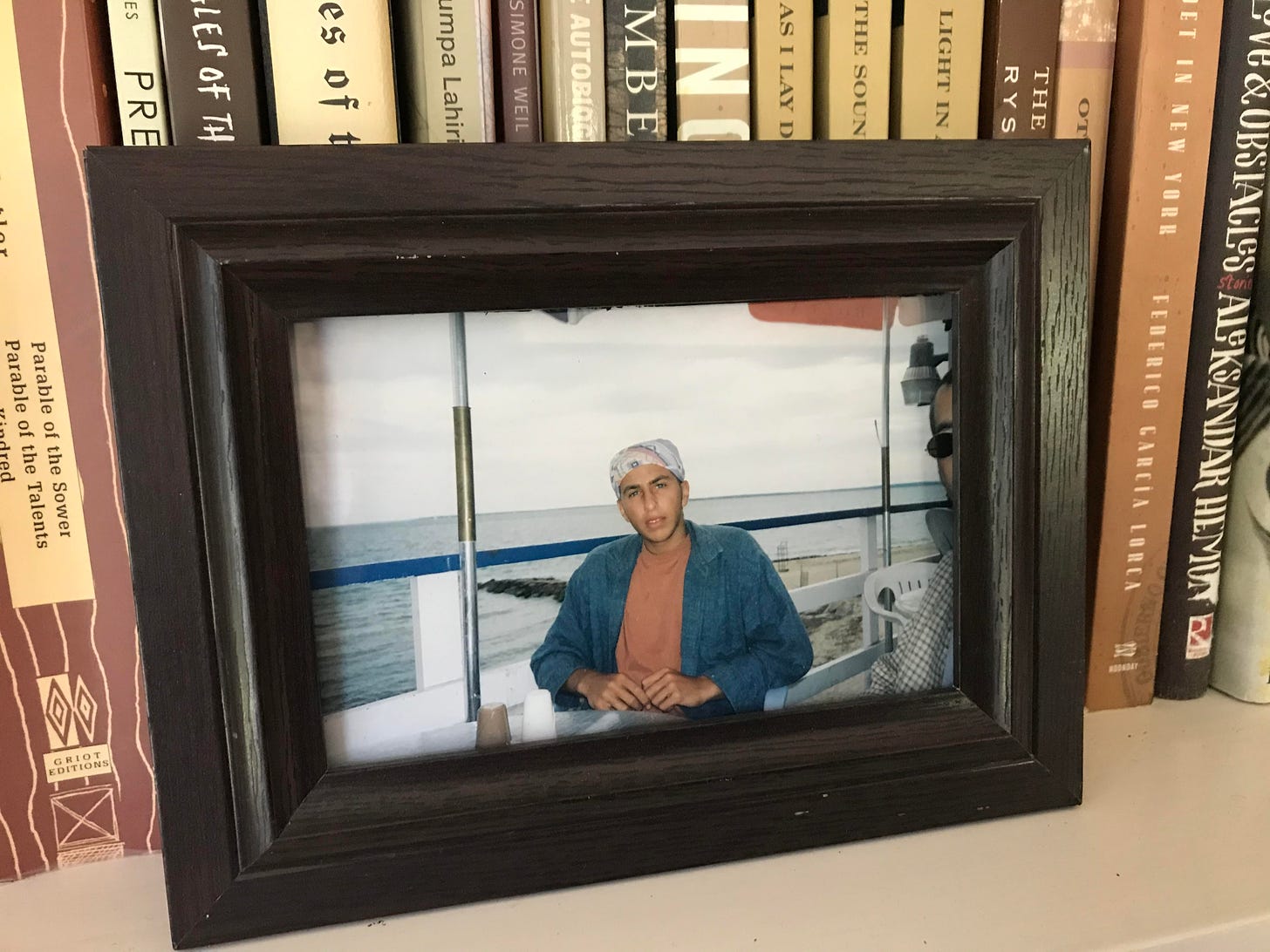

AM: My father spends a lot of time looking at old pictures. He finds joy in accessing those memories and remembering the good times and laughing. My mother does not do the same kind of reminiscing. I have a photo of my brother here in my studio, but it took me nine years to put it somewhere I could see it instead of taking it out twice a year. It was only after I wrote this book that I was like, "You know what, I'm framing this photo. I'm looking at this photo every day."

RS: Siblings are some of the most long-term witnesses to our lives. What is the hardest part of losing your witness?

AM: There is an expectation that your siblings will always be with you. There is something written into the DNA that is a kind of sharing that goes beyond words and transcends the relationship in some way. You understand that they are kind of the closest mystery but most like you biologically. David and I were very dissimilar in some ways, but there was a connection forged over so much time in the same household, under the same roof.

Whatever the circumstances of your upbringing, they shape you in different ways, but they are a shared input. David was by no means a writer, but we shared a lot in terms of the forging of a sense of humor. A very important person in our household growing up was Dave Barry, who at the time was a Miami Herald columnist. My father who worked at the Boston Globe would print it out off the AP wire and bring it home for us to read. Thirty-five years later, I write books with Dave Barry. He's a friend. That trajectory and it feels incomplete because I can't say to my brother, "Yo, I'm writing a book with Dave Barry. Like how crazy is that?”

RS: Your daughter was three when David died. How old was she when you shared the details with her and what was that moment like?

AM: It wasn't long ago [she’s nearly 13]. It was in anticipation of the fact that this book was about to exist in the world. I think about my children's mental health and the shame that caused my brother to hide his depression and the way that that decision contributed to his death. One of the mistakes my family made was thinking that depression was something you live with rather than something that can kill you. We watched my grandfather and his brother and my grandmother on the other side and this uncle and this cousin live with depression. I think that led us to believe that depression was a burden and something you shouldered and something that ebbed and flowed, but that you ultimately like lived with. And that's not always the case.

If it afflicts any of my children they need to have the words and tools that David never had. They need to be able to confide and share and shine a light on this.

Interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

What Siblings Day Means to Someone with a Dead Sister

by Kellyn Shoecraft

The first time I learned about the mere existence of Siblings Day was the spring after my sister’s unexpected death. This was pretty on-brand, given that every day since Alison collapsed unexpectedly felt like an alternate reality defined by life’s cruelest joke.

“Oh, your sister defied the odds and is in complete remission from her super scary cancer? I’m gonna go ahead and have her die from a side effect of a blood thinner! Mooohahaha!” And “Oh, you and your sister are closer than you’ve ever been in your lives? She’s (finally) your best friend? I’m going to snatch her from you forever!” And “What’s that? Your sister has a 21-month-old son and just last week had a meeting with an agency about ways of expanding her family after her hysterectomy? Scratch that plan!”

On the first Siblings Day I’d ever noticed, I found myself bombarded with photos of happy, vivacious siblings; just one of many experiences that highlighted the gaping hole in my life.

Most of us assume that SD (let’s just call it that, shall we?) is another unnecessary cultural norm birthed from social media — like taking photos of our food or artsy pictures of our feet. This is sort of true — SD first went viral on Twitter in 2012. But what most don’t realize is that Claudia Evart, the woman behind the idea and the nonprofit backing it, started SD in 1995 in honor of her dead siblings. Her sister, Lisette, died at 19 in a car accident. Her brother, Alan, died at 35 (reason unknown despite my expert Googling skills). Siblings Day is always on April 10th, Lisette’s birthday. The goal of the Siblings Day Foundation is to honor “siblings and the bond that is forever a special gift,” and to make April 10th as legitimate as Mother’s and Father’s Day.

Ironically, though, SD doesn’t feel like a safe space to honor the siblings that died too soon. That’s because this day has been taken over by social media, and most social media users are young(ish). Most young(ish) people don’t have dead siblings.

What sucks about people with “alive” siblings is that they usually don’t realize how easy it is to get punted to the other side of the line. We all think, at some point, about how we will outlive our parents. But we rarely, if ever, think about outliving our siblings. My dad died when I was 20 so I was supposed to be someone who ‘got it.’ I thought I knew about the insecurity of life. After my dad’s death, my new greatest fear was that my mom would die too. I woke up in deep sweats from nightmares that she had been murdered. I enabled tracking on her phone so I could keep tabs on her whereabouts. My sister and I used to joke that our mom drove like Cruella Deville, so I obsessively refreshed the GPS when I knew she’d be driving. In this high-anxiety state, not once did I ever consider that my sister would die. But she did die. Siblings die, and although it’s not that common, it happens.

Now that I know where to look for fellow surviving siblings, I’ve learned we’re really all over the place. I’ve met siblings whose brothers and sisters died before they were born, in childhood or as young adults. I’ve met siblings with multiple dead siblings. I have met others like me, who have lost parents and siblings.

What is hardest for me about SD? The attitude around it feels flippant. People post embarrassing childhood photos of their siblings and I know that they, as I did for many years, assume their sibling is a lifelong constant. Now that I’m of an age where friends have multiple children, I often see photos of tiny siblings, with captions about how they’re partners in crime for life. Hopefully they will be...but maybe they won’t.

Sibling death leaves you unmoored. Siblings are our life partners in the truest sense of the words, and though you may be polar opposites, they should be a mirror as you age. Even if you never got along, you have a shared history. You may both be nostalgic for the same childhood picture books or remember the same jingles from old TV commercials (my sister and I liked to sing, “My way is Hanes her way!” with a lot of attitude.).

My message to everyone with a sibling? If you have one who is alive and healthy, you are so very fucking lucky. Because a sibling with longevity is not guaranteed. When they die, you lose the security of your past and the base for your future.

On this Siblings Day, I’m sending love to all of those who have died too soon, and the surviving ones walking around with a huge piece of themselves forever missing.

Kellyn Shoecraft admins a take-over style Instagram account where those who miss their siblings can feel a little less alone. She is also the founder of Here For You, a company trying to change the way people support each other through life's most difficult experiences.

Upcoming Member Events - subscribe to register

📆 Mindfulness: Tapping into Self-Compassion (April 14, 12 pm ET)

🍪 Communal baking with A Mighty Blaze’s Rachel Levy Lesser (April 29, 7 pm ET)

ICYMI 🙈

Technology Is Impacting Grief: But is It Helping? - for everyone

I’m an Urgent Care Doctor. A Year Into the Pandemic, I’m Running on Empty. - for everyone

Register for our April sessions - members only

The Year We Lost Touch: A Year of Covid-19 - for everyone

Grief Deserves Its Own Soundtrack: So We Made You One. 🎵 - members only

My Sudden Onset Only Child Syndrome - for everyone

A Little Advice for the Heartbroken Club - for everyone

The Return of Hope - for everyone

Call It Grief and See if It Changes How You View It - for everyone

Want more? Become a Modern Loss member.

👯 Access to our peer-to-peer Facebook group

📆 Virtual Events (yoga for grief support, mindfulness meditation, therapist-led sessions and even some communal baking)

📝 Exclusive author conversations

🌟 Premium Content